Family Planning: A Significant Opportunity for Impact

This post was written as MHI was being founded in August 2022 as part of our research into the potential impact of family planning work and the best opportunities in this area of work. It provides an overview of our reasoning for pursuing work in family planning, and postpartum family planning specifically.

This was submitted to Open Philanthropy’s Cause Exploration Prize and originally published on the EA Forum.

Summary

- 218 million women in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) lack access to modern contraceptives.

- Lack of contraceptive access resulted in 85 million unintended pregnancies in 2019. Pregnancy-related complications are a major cause of death and disability in LMICs, with around 300,000 women and girls dying of pregnancy-related complications each year. Other negative outcomes of unwanted pregnancies include health risks for newborns, decreased autonomy, and negative economic impacts for families and communities.

- There are several highly cost-effective existing interventions in this space, such as radio messaging and integrating family planning services into postpartum care, that are comparable or even more cost-effective than existing GiveWell top charities.

- While there is substantial investment in this space by non-EA actors, there remain highly neglected geographies and significant outstanding opportunities, particularly for a funder focused on maximising impact and cost-effectiveness.

Importance

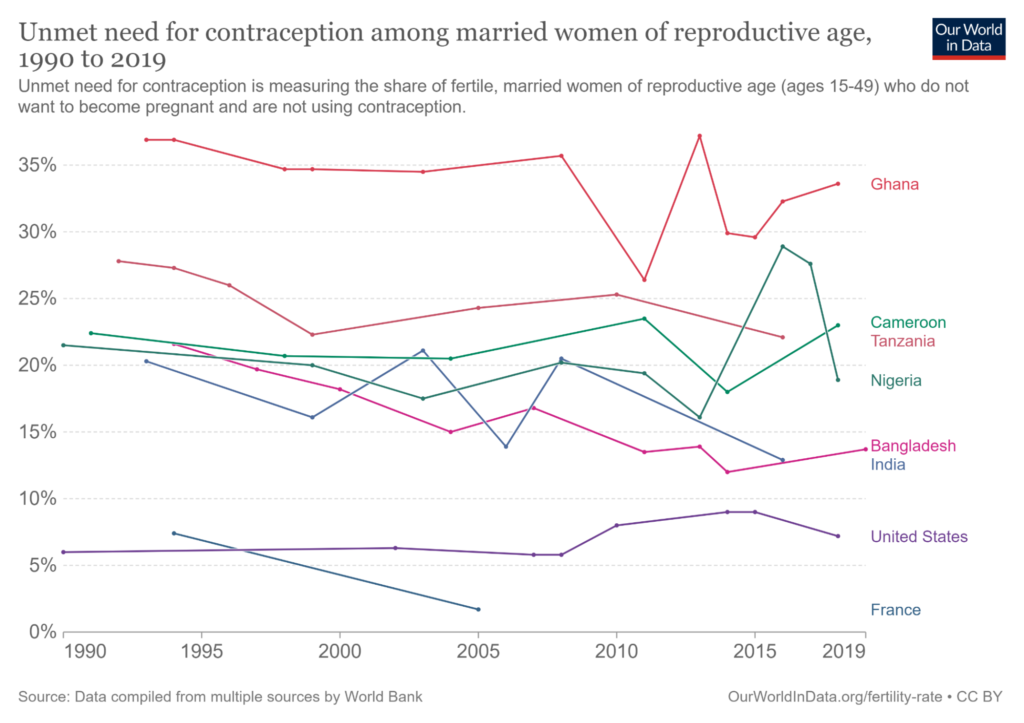

1 in 10 women of reproductive age worldwide want to postpone or avert a pregnancy but are not using modern contraception (UN DESA, 2020). This unmet need for family planning means that an estimated 218 million women in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) lack access to modern contraceptives (Guttmacher, 2020). Unmet need results from a range of reasons, including limited access to services, particularly among young, poor, and unmarried women; misinformation concerning side effects; and cultural or religious opposition (WHO, 2020).

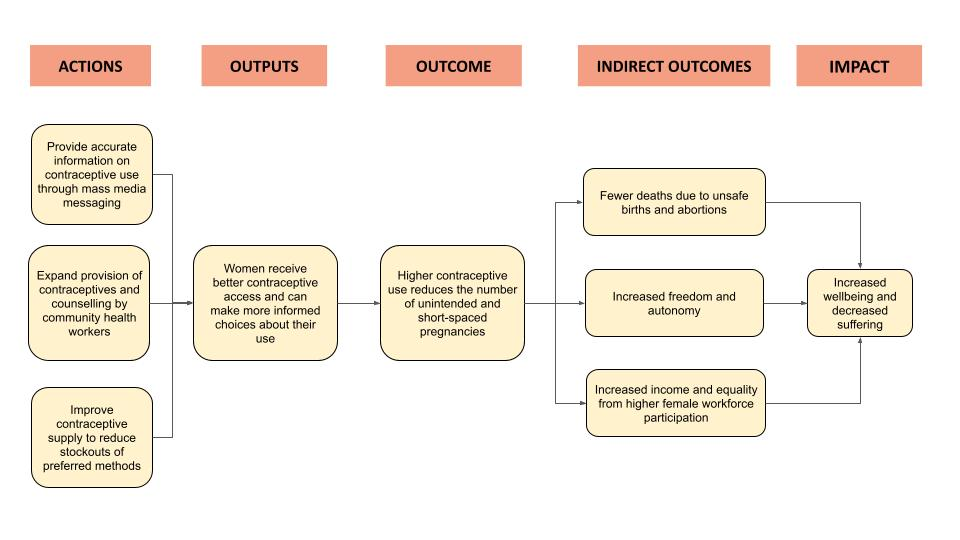

Lack of contraceptive access resulted in 85 million unintended pregnancies in 2019 (Sedgh et al., 2014). Unintended pregnancies lead to a number of negative effects. They are associated with higher maternal and neonatal death and disability from pregnancy and childbirth (Dehingia et al., 2020), as well as higher rates of unsafe abortions (Kantorová, 2020). Unintended pregnancies also lead to significant losses in autonomy for women who are unable to exert control over their lives. This has a knock-on effect on their income due to decreased earnings and increased expenses (Schultz, 2009), with consequent negative effects on national economies (Canning et al., 2012).

Maternal and Neonatal Health Impacts

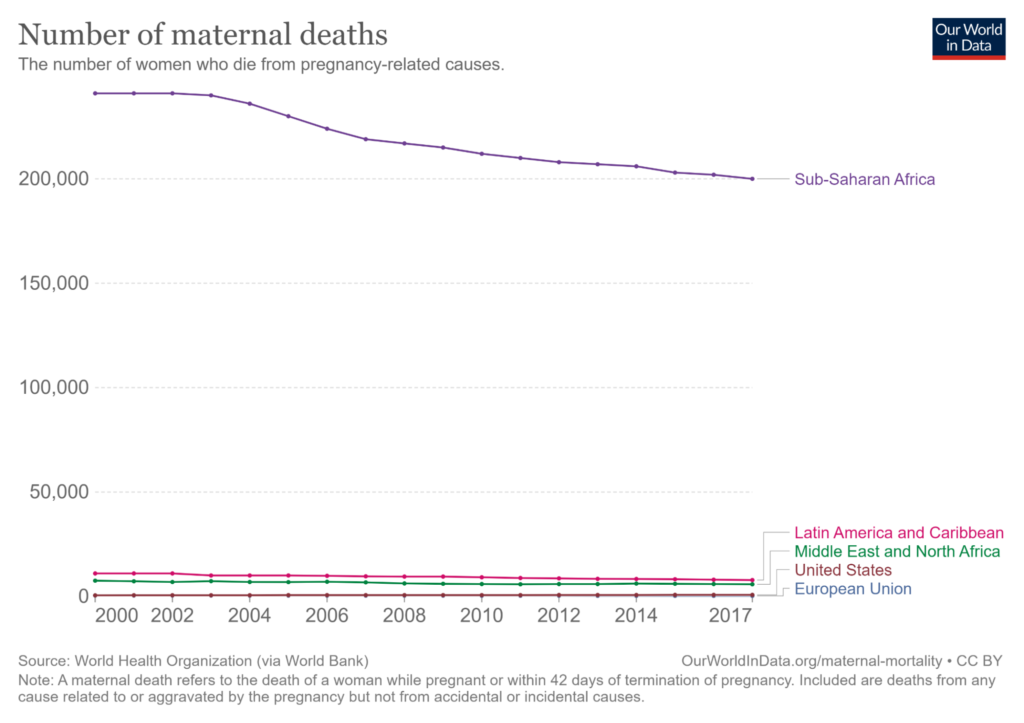

Pregnancy-related complications continue to be a leading cause of preventable death among both mothers and children, with almost 300,000 women and girls dying due to pregnancy and childbirth in 2017 (WHO, 2017). The risk is particularly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for more than 2/3 of global maternal deaths (Our World in Data, 2013).

Contraceptive use reduces the DALYs lost through pregnancy-related complications by reducing the total number of births, allowing adolescents to delay births, and allowing for birth spacing. Pregnancy and childbirth are more dangerous for those aged 10-19, with particular dangers for girls under 15 years old. However, pregnancy remains common among adolescents in LMICs, with complications from pregnancy and childbirth constituting the leading cause of death for women aged 15 to 19 (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2014). These pregnancies also pose risks to newborns, as rates of preterm birth and low birth weight are much higher among babies born to young mothers (Neal et al., 2018). Contraceptive access mitigates these risks by allowing young women to delay births until the risks are lower (WHO, 2017).

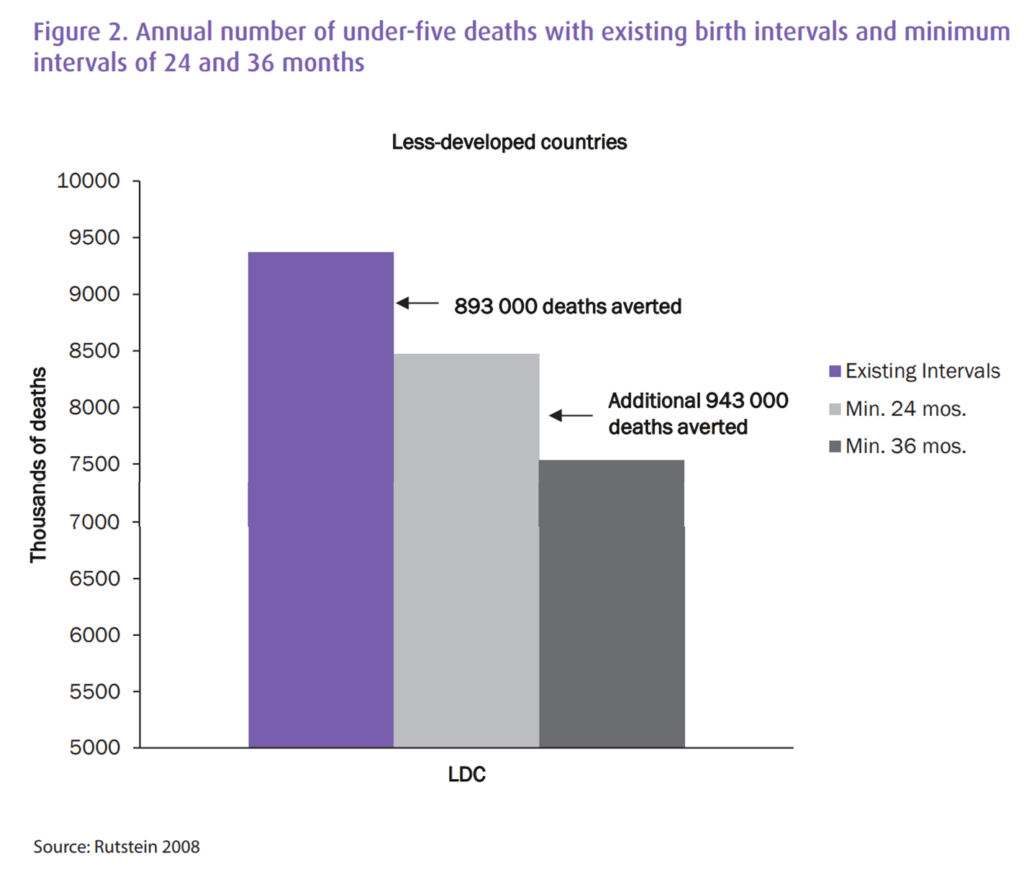

Short-spaced pregnancies – when women give birth within 2 years of their most recent birth – present substantial health risks to both mother and child, yet are fairly common in LMICs. Although the exact mechanisms aren’t clear, giving birth within a shorter timeframe compromises the mother and child’s nutrition (Wendt et al., 2012) and increases the riskiness of the pregnancy. Short-spaced births are strongly associated with increased risk of low birthweight, stillbirth, and neonatal death (Schummers et al., 2018; Gemmill and Lindberg, 2014).

Cleland et al. (2006) estimate that comprehensive access to family planning could avert more than 30% of maternal deaths and 10% of child mortality. Despite this, birth spacing is often underutilised. Misconceptions concerning postpartum fertility, lack of awareness of the health benefits of birth spacing, and lack access to preferred methods of contraception all contribute to the continued prevalence of short-spaced pregnancies (Dev et al., 2019).

Despite legal barriers and social stigma, more than a third of unintended pregnancies in sub-Saharan Africa end in abortion. The bulk of such abortions are unsafe, carrying with them serious threats to women’s health (Guttmacher, 2020). Recent analysis suggests that unsafe abortions are the cause of 5-13% of all maternal deaths globally (UNFPA, 2022). Increased contraceptive access would reduce uptake of unsafe abortions and the corresponding threats to women’s health.

Decreased Autonomy

More broadly speaking, unintended pregnancies compromise women’s autonomy. The decision of whether to have a child has wide-ranging effects on women’s lives, bearing on questions of health, education, and employment. Providing women with the tools to delay or avert a pregnancy empowers them with a greater level of control over their bodies and their lives. The fact that so many unintended pregnancies in LMICs end in abortion despite the associated dangers and social stigma suggests that many women have strong preferences against additional births that are currently being undermined due to lack of access to contraception.

The autonomy effects of family planning are difficult to quantify but clearly significant, given as they relate to women’s control over fundamental aspects of their bodies and their lives, with a similarly wide range of hard-to-measure benefits as interventions such as unconditional cash transfers.

Income and Economic Development Impacts

Unintended pregnancies have negative economic effects on both individual families and on national economies more broadly. Modelling the economic benefits of a reduction in total fertility rate by one child per woman in Nigeria, Canning et al. (2012) found this would increase GDP per person by 13.2% above baseline forecasts after 20 years, and 25.4% after 50 years factoring in long-term effects. On an individual level, the 19-year Matlab family planning study in Bangladesh raised women’s average wages by a third (Schultz, 2009).

Broadly speaking, a reduction in fertility rates produces a ‘demographic dividend’ of a high working population relative to the number of dependents. This can provide “a window of opportunity for rapid economic growth and a boost in per capita income” (Guttmacher, 2019).

Environmental Impacts

“[P]oor reproductive health outcomes and population growth exist hand-in-hand with poverty and unsustainable natural resource use” (Yavinsky, 2015). Providing universal choice over family size would likely lead to reduced population growth, with significant flowthrough benefits for the environment (Starbird et al., 2016).

Project Drawdown (n.d.), which evaluates leading environmental solutions, lists ‘Family Planning and Education’ as the 3rd most effective solution available for reducing CO2 emissions out of 90 reviewed.

Tractability

There is strong evidence that family planning programmes produce large increases in contraceptive uptake, alongside decreases in fertility rate, unmet need, and maternal mortality rates. This suggests that family planning is a highly tractable area in which to work.

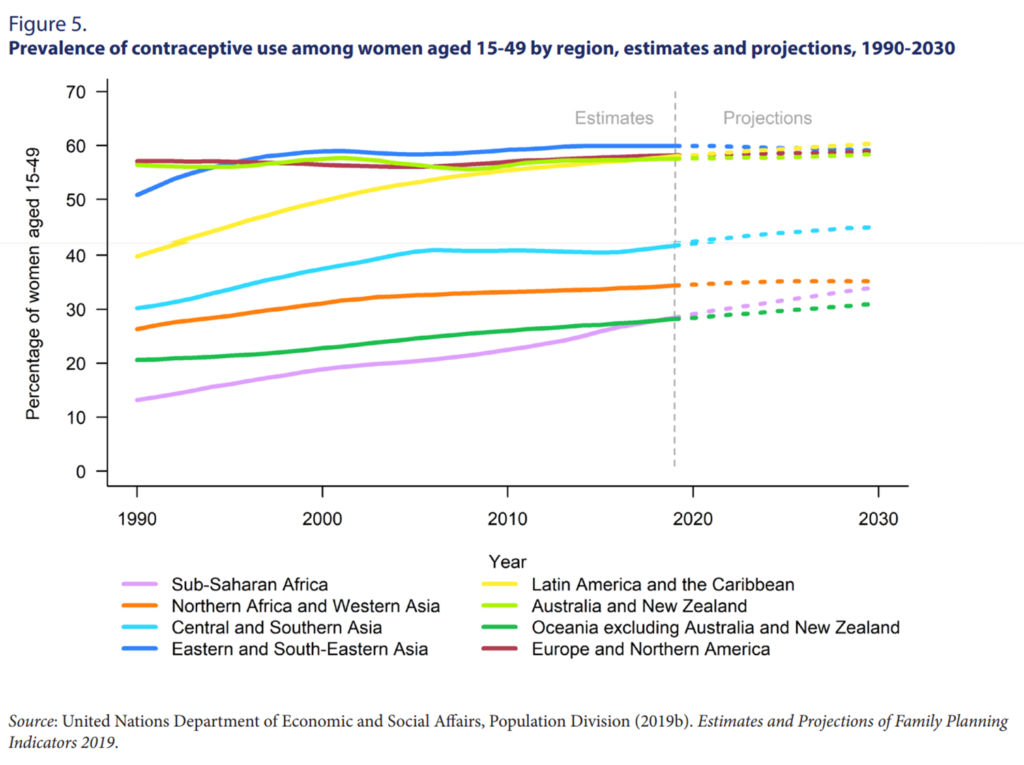

In 2015, 64% of women of reproductive age used contraception globally, with family planning charities playing ‘a key part in raising the prevalence of contraceptive practice from less than 10% to [more than] 60%’ over the last 40 years (Grant, 2016). To take one example, total fertility in East Asia fell by more than three children per woman between 1970 and 2019 (OECD, 2022) while contraceptive prevalence rose by 33% over the same period (Haakenstad et al., 2022).

However, contraceptive uptake remains low in many countries, presenting a significant opportunity for further success and action. This investment can be highly cost-effective. For example, Kennedy et al. (2013) estimated that a $9 million investment in contraceptive access in Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands could meet family planning needs across the two countries. This would produce $112 million in economic benefit while averting 2,500 maternal and child deaths – a cost of $3,600 per death prevented.

There are well-evidenced programmes for increasing contraceptive uptake with demonstrable results. One example comes from the ‘Matlab’ study across 140 villages in Bangladesh over a 20-year period. Through a mixed-method approach, child-to-woman ratios were 16% lower in villages with an outreach programme than in those that had access only to standard government family planning clinic services, after adjustment for village and year fixed effects (Canning et al., 2012). Further evidence for effective family planning interventions is summarised in the ‘Family Planning: High Impact Practices’ briefs compiled by a panel of leading stakeholders, including the WHO, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and USAID.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a particularly promising geography for family planning, as it has the highest fertility rate in the world as well as the highest unmet need for family planning. Contraceptive rates across Africa are less than half of the global average (Grant, 2016), and by 2030, over half of young women with unmet need for family planning will live in the region (Gahungu et al, 2021).

The most promising family planning interventions target the root causes of unmet need for family planning, including lack of accurate information, limited access to services, low-quality services, and cultural opposition. A full exploration of all possible avenues for family planning interventions is beyond the scope of this writeup, but we will now briefly explore two of the central drivers of low family planning uptake–lack of accurate information and limited access to services–and investigate possible interventions in these areas.

Problem: Lack of Accurate Information around Family Planning

Lack of accurate information concerning family planning methods is a key driver of unmet need for family planning. Numerous studies have indicated a substantial knowledge gap concerning family planning in many LMICs (Family Planning: High Impact Practices, n.d.). Misconceptions surrounding contraceptives are often common, such as beliefs that contraceptives cause infertility and cancer (Adongo et al., 2014). Such misconceptions lead to decreased contraceptive uptake.

A range of interventions dedicated to disseminating accurate information concerning family planning have been tested, to varying results. The most promising interventions include mass media, interventions promoting healthy couples’ communication, social norm-based interventions, and interventions targeting individual knowledge, beliefs, and self-efficacy (Family Planning: High Impact Practices, n.d.).

Example Solution: Mass Media Campaigns

Of these interventions, mass media stands out for its cost-effectiveness and scalability. Other interventions in this space involve the costs of running individual or group counselling sessions, or training peer educators who can reach a limited number of clients per week. In contrast, mass media interventions can reach hundreds of thousands to millions of people at a set, low cost. Furthermore, mass media campaigns can be scaled to reach multiple regions or entire countries much more easily than other interventions, greatly increasing their potential impact.

Strong evidence suggests that well-run mass media campaigns increase contraceptive uptake and decrease birth rates. Across 9 studies included in a systematic review that reported change in modern contraceptive use, the effect size ranged from 5-27% increase in uptake (Family Planning: High Impact Practices, n.d.). For example, Glennester et al. (2021) found that a 2.5 year mass media campaign reaching 5 million people led to a 5.8% increase in modern contraceptive uptake and 10% decrease in birth rate.

Example Organisation: Family Empowerment Media

Family Empowerment Media (FEM) launched in September 2020 through the Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Program (Charity Entrepreneurship, 2022). They work to help couples in LMICs plan their families by implementing radio-based social and behavioural change campaigns, leading to higher uptake of contraceptives, fewer unintended pregnancies and improved maternal and child health.

Through their work in Kano in Northern Nigeria, FEM reach more than 5 million listeners more than 10 times a day, with ads and longer format shows, including stories, testimonial shows and serial dramas. A one-minute long ad provides contraceptive information to this audience base for just $14.40 (Family Empowerment Media, 2022).

Early evidence indicates that FEM’s radio programs are highly effective. In the time period overlapping with their pilot campaign, the contraceptive uptake in Kano increased by 75%, from 8pp to 14pp, corresponding to ∼250,000 new contraceptive users (PMAdata, 2022). This is twice the increase measured in the last 5 years combined. This work was conducted in a region where around 1% of all pregnancies cause a maternal death (Meh et al., 2019). FEM is aiming to conduct an RCT to validate their impact further, using a new technology they have invented.

Scaling their programming over the next four years, FEM expects to avert a maternal death for ∼ $2,600 while operating in 10 Nigerian states and reaching 16 million people (Charity Entrepreneurship, 2022). This would make FEM’s cost effectiveness comparable with other Givewell recommended organisations, solely on the basis of cost per life saved (Giving What We Can, 2016).

FEM has closed their 2022 funding gap and is now raising $1.1 million to scale their programmes to three new regions in 2023 (Charity Entrepreneurship, 2022). A commitment of $7.0 million would fund FEM’s ambitious scaling plans over the next four years, preventing ∼3100 maternal deaths and ∼340,000 unintended pregnancies. FEM is doing proof of concepts (short campaigns) in three new regions by the end of 2022, and will have an even better understanding of the potential and cost effectiveness of the intervention at scale then.

Problem: Limited Access to Services

Another key driver of unmet need for family planning is that many women simply lack physical access to contraceptives. This results in part from the reality that healthcare systems in many LMICs are generally under-resourced. However, challenges specific to family planning abound, some of which are tractable through targeted interventions.

Given the complex breadth of reasons why access to contraceptives is lacking in many LMICs, the range of potential interventions is similarly broad. Some of the most promising interventions include expanding family planning coverage by community health workers, integrating family planning into postpartum and post-abortion services, mobile outreach services, advocating for domestic public financing of contraceptives, and addressing supply-chain issues in order to reduce contraceptive stock-outs (Family Planning: High Impact Practices, n.d.; Family Planning: High Impact Practices, n.d.).

Depending on the execution approach taken, many of these interventions could be highly cost-effective and impactful. For example, Advance Family Planning has successfully advocated for the expansion of family planning programs across several LMICs. Meanwhile, IntraHealth International has strengthened supply chains in countries such as Senegal in order to reduce contraceptive stock-outs.

This writeup will briefly explore one intervention targeting limited access to family planning services in greater depth, postpartum family planning, as Charity Entrepreneurship has identified it as a highly impactful intervention with strong cost-effectiveness.

Example Solution: Postpartum Family Planning

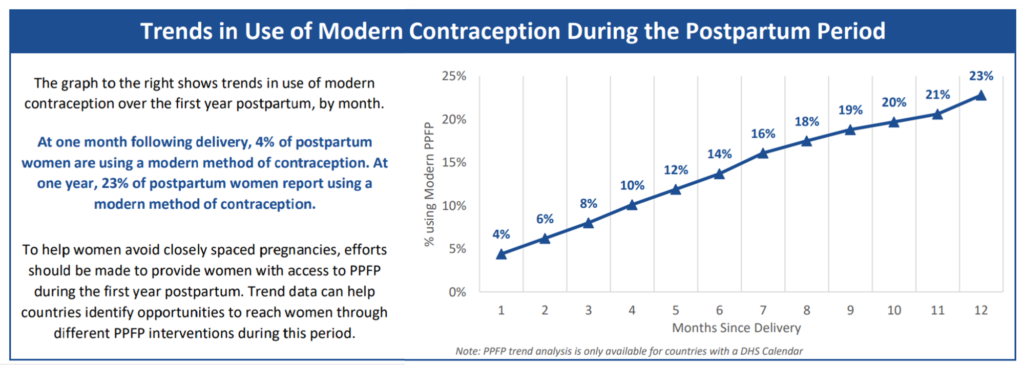

Postpartum family planning (PPFP) is the provision of contraceptive information and access during the period of care a mother receives at a health facility when giving birth (Family Planning: High Impact Practices, n.d.). This can be both in the immediate aftermath of childbirth and in the subsequent 12 months in conjunction with maternal and child health check-ups.

PPFP is considered a ‘proven’ family planning intervention by a panel of leading development organisations, including USAID, WHO and the Gates Foundation (Family Planning: High Impact Practices, n.d.). In a 2017 report evaluating immediate postpartum family planning, USAID found a 33% increase in contraceptive uptake across five programmes evaluated (Family Planning: High Impact Practices, n.d.).

Postpartum family planning is a particularly promising opportunity for several key reasons. First, it is effective in preventing short-spaced pregnancies by providing mothers with contraceptive access in the immediate aftermath of a birth.

As discussed previously, short-spaced pregnancies lead to higher mortality rates, with wide-ranging negative health consequences for both the mother and child (DaVanzo et al., 2007). Delaying all births until 24 months after a previous pregnancy could avert 893,000 child deaths across 52 LMICs (Rutstein, 2008).

Second, the postpartum period is one of the only points at which many women in LMICs will interact with the formal healthcare system. This period is one of the few opportunities for women to safely access a wide range of contraceptive options. Despite this, contraceptive uptake in the postpartum period is consistently lower than average national rates (Pasha et al., 2015; Track20, n.d.).

Partnering with governments in LMICs to integrate family planning into postpartum care is a highly cost-effective way to increase uptake of family planning services (Zakiyah et al., 2016). By providing both information and access to services, it addresses multiple root causes of unmet need for family planning. By targeting women in the postpartum period, it reaches women at higher risk of short-spaced pregnancies. Furthermore, partnering with governments creates the opportunity for an organisation to shape policy at a regional or national scale, greatly increasing potential impact.

Charity Entrepreneurship modelled the cost-effectiveness of a PPFP charity operating in Ghana. They estimate that this charity could reach 2.5 million women across 8 years at a cost of $39 per additional contraceptive user and $67 per unintended birth averted. The low costs per additional user and birth averted suggests that postpartum family planning is a cost-effective way of improving health, increasing autonomy over fundamental choices, and improving income for families and communities.

Existing organisations–such as Jhpiego and IntraHealth International–have engaged in advocacy and technical assistance in order to promote postpartum family planning in a number of LMICs, but substantial gaps remain.

Charity Entrepreneurship is launching a postpartum family planning charity through their Summer 2022 Incubation Programme to address this gap. Starting with a pilot programme in sub-Saharan Africa in late 2022, this charity will aim to partner with governments to scale PPFP training and support for community health workers nationally.

Neglectedness

Family planning has not received philanthropic resources commensurate with its massive scale (Grollman et al., 2018). Recent investments in the sector have helped to make the gap less severe, but the mismatch between the problem and the resources dedicated to addressing it remains substantial, and a range of cost-effective interventions remain untapped.

Historically, only limited resources have been allocated to family planning interventions, with one estimate suggesting that donor assistance amounted to only $0.17 per woman of childbearing age in developing countries in 2008 (Tsui, 2010). The Family Planning 2020 Partnership – subsequently retooled as FP 2030 – has led to increased resources dedicated to family planning. However, these resources remain insufficient to address the need present (Guttmacher, 2019).

The need for further investment in family planning is underlined by the fact that the number of women with an unmet need for family planning is growing rather than shrinking (UN DESA, 2020). Though the percentage of women with an unmet need is slowly decreasing, the total number of such women is growing due to global population trends, with an increasing proportion of people living in areas with high levels of unmet need for family planning.

Funding in the family planning space is not consistently oriented towards the most cost-effective interventions nor the most neglected geographies. Cost-effectiveness is only one of many considerations for major funders within the space, and this is reflected in the programs receiving funding (Fan et al., 2017). Condoms and other short-term contraceptives have received substantially more investment than longer-acting contraceptives (UNFPA, 2022) despite the likely greater cost-effectiveness and longevity of the latter (Ngacha and Ayah, 2022; Trussell et al., 2009). Additionally, the most cost-effective interventions have not received substantial funding, with only minimal funding going to interventions such as mass media and postpartum family planning.

Geographically speaking, funding has not been as targeted toward sub-Saharan Africa as the distribution of unmet family planning need would suggest, with major donors – such as the UN Population Fund – dedicating a surprising amount of resources to other geographies (UNFPA, 2021).

These factors mean that there is significant low-hanging fruit remaining in the family planning space; that is, there are a number of areas where an effectiveness-minded funder could catalyse significant impact.

Finally, it’s worth noting that non-governmental funders are particularly important within the family planning space due to the politicisation of abortion and family planning services. Some national governments are unwilling to fund family planning or provide funding with substantial strings attached, meaning that non-governmental funders are particularly important in this space (Grollman et al., 2018).

Uncertainties & Downside Risks

To what extent will contraceptive use increase without targeted interventions?

Some may argue that family planning interventions shouldn’t be a priority given that demographic and development trends have led to increased contraceptive use and corresponding decreases in fertility rate even in the absence of targeted family planning efforts. And, indeed, historical trends suggest that increased education and economic growth make a significant contribution to higher contraceptive uptake and decreased family size.

However, family planning interventions appear to produce significant additional effects, notably accelerating and extending progress. A historical analysis by DaVanzo and Adamson (1998) found that family planning programs have been responsible for around 43 percent of the decline in global fertility from 1965 to 1990.

Additionally, contraceptive uptake in certain geographies lags far behind global trends. Most notably, this is the case for many parts of sub-Saharan Africa where contraceptive uptake remains far lower than global averages (Grant, 2016). This presents a significant opportunity for influence that is likely to be robust to global trends.

Existing evidence for benefits of family planning may undersell its value

It is hard to quantify some of the most significant benefits of family planning. Increased

autonomy is among the strongest benefits of expanded access to family planning, yet we found very little measurement of autonomy in health and development research. The Relative Autonomy Index (RAI) provides one recent example of the kind of measure that may better illustrate the full extent of benefits arising from family planning (Vaz et al., 2016; Gram et al., 2017).

Similarly, control over one’s fertility is likely to produce significant effects on subjective wellbeing. At a minimum, we can expect a reduction in unintended pregnancies to produce a decrease in postpartum depression and consequent increase in subjective wellbeing. However, we could not find robust measurement of the subjective wellbeing effects of contraceptive access in the literature.

These benefits make it more challenging to fairly compare family planning against other interventions. How can the autonomy effects of family planning be measured against those of other autonomy-improving interventions, such as cash transfers? How can the overall effects of family planning be compared against other interventions with little to no autonomy effects? Answers to these questions, however provisional, would allow comparisons across cause areas to be made more fairly and consistently.

Further investigation

While we think this report offers a solid introduction to the opportunities within family planning as a cause area, there are additional questions that would be worth investigating. A more thorough evaluation of how current funding is allocated by large grantmakers would help to identify a wider range of particularly promising programmes.

Similarly, a longer research process assessing the cost-effectiveness of a range of existing organisations would be likely to produce a longer list of specific grants that Open Philanthropy could disperse. Family planning is a large area, with both significant room for additional funding and a large number of existing actors. As such, we believe it is likely that there are more organisations than those we have highlighted in this report whose work would be highly impactful if given the funding to scale up.

Finally, it fell beyond the scope of this report to fully explore the evidence for the benefits of family planning in less-researched areas. In particular, we think that further study and measurement of increases to subjective well-being and autonomy from contraceptive access may provide additional compelling evidence for the value of family planning as a cause area.

Conclusion

Unmet need for family planning services is a substantial problem, leading to significant death and disability for mothers and children, decreases in autonomy, and negative economic effects on families and national economies. Cost-effective interventions such as radio-based messaging and postpartum family planning, among many others, offer the possibility of addressing the harms created by unmet need for family planning.

Progress in family planning appears highly tractable yet comparatively neglected by the EA movement compared to many other large-scale global health and development investment programmes. On a global scale, expanding contraceptive access could prevent 2.5 million maternal deaths, 73 million child deaths, and 16 million stillbirths by 2035 (Stenberg, 2014).

By investing in cost-effective and scalable family planning solutions, Open Philanthropy could lead this work and have a transformative positive impact.

Note: The authors of this report plan to launch a postpartum family planning charity after evaluating several promising charities through the 2022 Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Programme. We think that family planning is a strong cause area that includes a number of highly promising interventions, including but certainly not limited to PPFP. Additionally, the section on Family Empowerment Media was edited by their staff for accuracy.