Pilot - Research Study

An overview of MHI’s major project of 2023: delivering a study evaluating two family planning counselling interventions in partnership with Norsaac and the Ghana Health Service, and with ethical approval from the Navrongo Health Research Centre.

This page provide key excerpts from our report analysing the project. To download the full report, please click here.

When?

Where?

August-December 2023

Karaga, Zabzugu, Yendi, Kpandai, Bimbilla, and Gushegu hospitals – all in the Northern Region of Ghana.

Executive Summary

- In this project, the Maternal Health Initiative (MHI) and Norsaac worked together to implement a programme aiming to increase contraceptive knowledge and uptake. This programme focused on training nurses and midwives on delivering an adjusted model of contraceptive counselling integrated into routine postpartum appointments.

- This was a pilot project in which we aimed to compare the value of one-to-one family planning counselling during routine postnatal care sessions (PNC) against the value of short messaging and family planning referral integrated into child welfare clinic sessions (CWC)

- Endline data suggests that the PNC program produced an increase in contraceptive uptake, with no clear change observed in the CWC program. Due to inconsistencies between data sources and overall data quality concerns, we have low confidence in the extent of positive impact from either program.

- Research prompted by our pilot results suggests that contraceptive uptake in the early postpartum period may be significantly less valuable than expected. This is due to the high level of pregnancy prevention many women are likely gaining from unexpectedly high rates of breastfeeding and sexual abstinence.

- Based on the results presented in this report alongside further research and engagement with experts, we conclude that neither project is worth further implementation or scaling at this time.

Overview

Context

Ghana has low contraceptive uptake with a national average of 33.8% (ARHR, 2022), much lower than the world average of 48.5% (United Nations 2019). Furthermore, Ghana has an unmet contraceptive need of 30%, meaning that many women would like to control the frequency and number of pregnancies but are not using contraception (Asah-Opoku et al. 2023).

Over recent years in the Northern Region, there has been a declining family planning acceptor rate (2018: 31.4%; 2020: 28.2%; 2022: 25.5%). This falls short of the national target of 40%, and behind other nearby regions (e.g. North East was 35% in 2022). One potential barrier to higher rates of family planning is insufficiently good quality counselling, with women not being adequately informed about potential side-effects (Rominski et al, 2017), and low levels of shared decision-making (Advani et al, 2023).

Postpartum family planning (PPFP) – that is, integrating family planning guidance into postnatal care and/or child immunisation appointments– has been found to be an effective way of increasing contraceptive uptake and reducing unmet need in other contexts (see: Wayessa et al. (2020) in Ethiopia; Saeed et al. (2008) in Pakistan; Tran et al. (2020) in the Democratic Republic of Congo; Tran et al. (2019) in Burkina Faso; Pearson et al. (2020) in Tanzania; Dulli et al. (2016) in Rwanda). It is the official Ghana Health Service policy that family planning should be included in postnatal care (Ghana Health Service, 2014). However, research indicates that consistency and quality of family planning services in the postpartum period varies in practice (Morhe et al. 2017).

Timeline

August – September 2023 | Phase 1 – Formative Research Refined program design through engagement with facility stakeholders and baseline data collection. Completed baseline data collection through structured questionnaires conducted with postpartum women at facilities, following up with clients 14 days after the initial questionnaires via mobile phone to assess contraceptive uptake. |

October-November 2023 | Phase 2 – Intervention Ran the training sessions in October 2023, beginning a process of implementing the intervention packages. This included an assessment of providers’ knowledge and attitudes towards family planning, and ongoing monitoring work to ascertain the quality of implementation. |

November 2023 – January 2024 | Phase 3 – Evaluation Conducted endline data collection through structured questionnaires conducted with postpartum women, both at the facilities and by mobile phone two weeks after the initial questionnaires. Questions used for data analysis were held the same as in the baseline surveying. This follow-up data was collected 6 weeks after the training sessions concluded, with subsequent collection of facility record data. |

Program Design

Introduction

This project aimed to test the value of individual PNC family planning counselling with the value of incorporating family planning counselling into CWC immunisation. As such, two separate training sessions were run, one focused on PNC and the other on CWC.

For the PNC session, staff attended from Yendi, Gushegu and Bimbilla hospitals in the Northern Region. For the CWC session, staff attended from Zabzugu, Kpandai and Karaga hospitals in the Northern Region. Both training sessions were held in Yendi, with providers invited overnight from their respective facilities.

Ethical approval was sought and obtained for the project in July 2023. This coincided with discussions with the Northern Regional Health Directorate to confirm the value and scope of the project, resulting in the project receiving the necessary approvals. Programming materials were designed by MHI’s team in collaboration with their network of international advisors, with consistent input and collaboration from the Norsaac team.

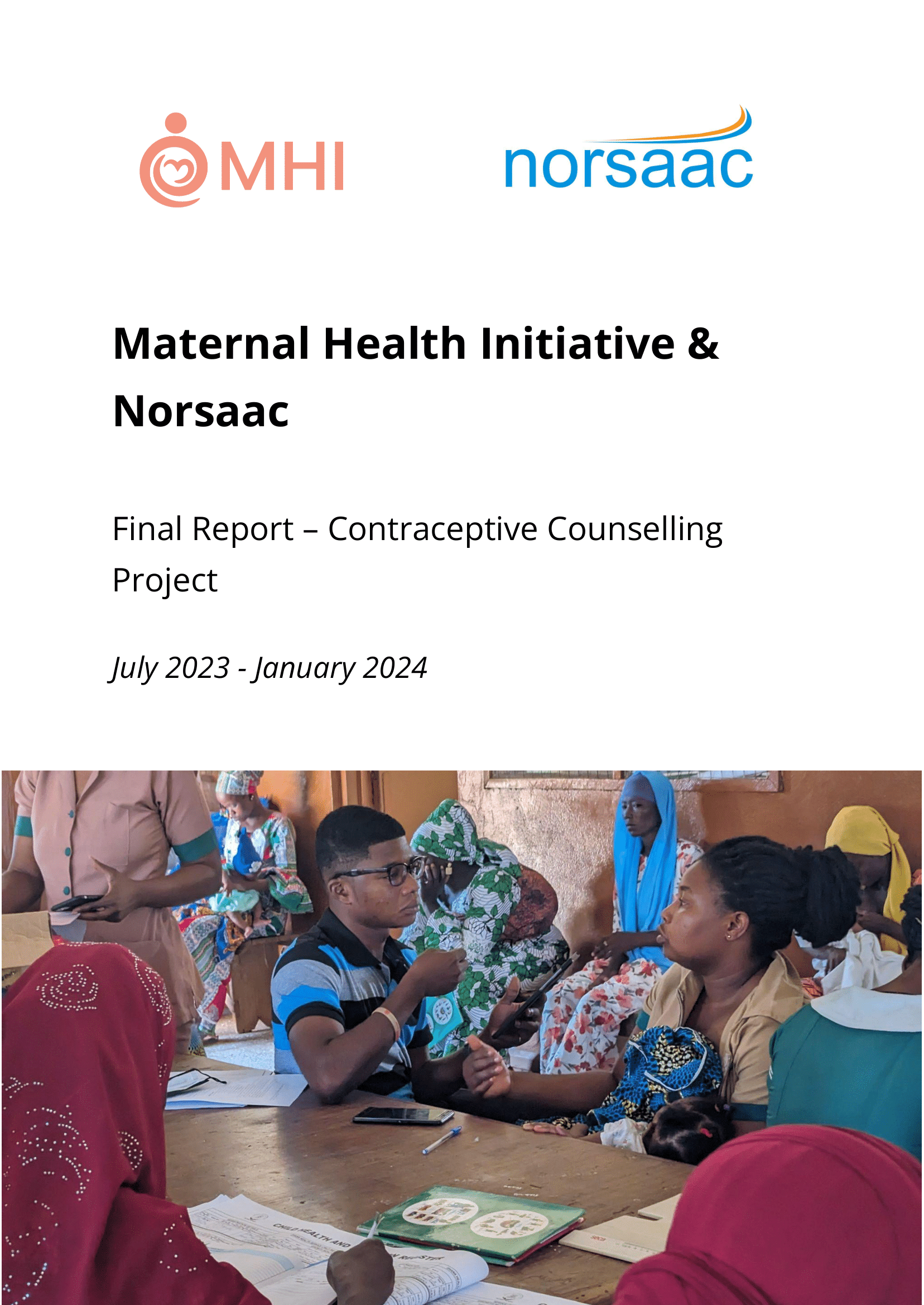

Members of the Norsaac surveying team conducting client interviews at some of the facilities where staff were trained.

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to ascertain the effectiveness of two intervention packages in improving the uptake of modern contraception among postpartum women. One package targeted improving family planning care at postpartum care sessions and the other targeted child immunisation appointments.

Secondary objectives included:

- Increasing knowledge of family planning among providers

- Increasing knowledge of family planning among women who attend child immunisation and postnatal care sessions

- Increasing the consistency of family planning information provision at child welfare clinic and postnatal care sessions

- Ensuring that women have the option to take up family planning at the same facility and on the same day as they attend appointments if they wish

Evidence

The two programming strategies outlined below were selected based on an extensive review of the evidence supporting different approaches to increasing contraceptive knowledge and uptake. Both approaches are supported by numerous randomised control trials (RCTs).

A study by Asah-Opoku et al (2023) in Accra concluded that one-to-one counselling as part of routine postnatal care sessions (PNC) was associated with a significantly greater uptake of contraception during the postpartum period compared to counselling between one provider and a group of clients. Further evidence for the effectiveness of integrating family planning into early postpartum care is presented in this High Impact Practices report.

Meanwhile, Dulli et al (2016) found that incorporating family planning services into routine child welfare clinic sessions as part of immunisation provision resulted in significantly increased postpartum contraceptive use. Positive outcomes have also been reported in Egypt (Ahmed et al, 2013), Malawi (Cooper et al, 2020), and Liberia (Cooper et al 2015).

Intervention Arm 1: Postnatal Care (PNC)

Providers at the PNC session were given a counselling guide, method cards, and a method information booklet. The focus of this intervention was to increase the frequency and quality with which family planning counselling is included in 1:1 counselling sessions.

To guide healthcare workers through a streamlined process of counselling, we provided them with a counselling guide specifically targeted at the postnatal period. This includes guidance on the safety of different methods at different stages after birth. Method cards were also provided to healthcare workers to ensure that counselling was interactive and client-centred.

Finally, each training attendee was given a method information booklet with an extensive explanation of family planning methods as reference material for continued learning and knowledge reinforcement.

Based on feedback from our earlier projects, we extended the depth of guidance in the method information booklet on side effect management and mitigation. We also updated the design of the counselling guide to make it as convenient to use as possible.

Intervention Arm 2: Child Welfare Clinics (CWC)

At the CWC session, providers were given a group talk flipchart, 1:1 counselling card, and referral cards for directing people to the Family Planning Unit. The intervention was designed to consist of two key components:

Group talk

Providers offer a group talk on family planning to women waiting for their child to be immunised following the flipchart. This group talk emphasises the range of methods available to clients, how to safely take methods and manage their side effects, and the benefits of receiving family planning counselling while at the facility.

1:1 interaction

While healthcare workers are providing any immunisations to the client’s child, they are encouraged to engage clients in very short 1:1 family planning counselling using the ‘birth spacing card’.

For clients interested in taking up a family planning method, the provider offers them a referral card to encourage them to visit the Family Planning Unit and highlight to the health workers at the unit that the client has already received some family planning counselling.

Results

Intervention Arm 1: Postnatal Care (PNC)

Summary

Across the facilities, the quality of implementation varied significantly. At Yendi, implementation was strong but the consistency of implementation appeared significantly worse at Bimbilla and Gushegu.

Based on a comparison of baseline and endline surveying, the overall incidence of 1:1 family planning guidance increased by 22% across the course of the project. There was no overall change in knowledge. Reported intention to use a contraceptive method did not shift during the project, with a 3% increase in reported contraceptive use based on in-person surveying..

A comparison of follow-up phone surveys (conducted 2 weeks after facility visits), suggests a 22% increase in contraceptive uptake. However, these results should be treated with significant caution due to possible sampling bias. Very high rates of reported abstinence suggest that change in contraceptive uptake at this point post-birth may be less useful in reducing unintended pregnancies than anticipated.

Intervention Arm 2: Child Welfare Clinic (CWC)

Summary

Across the facilities where the child welfare clinic model was tested (Zabzugu; Kpandai; Karaga), there was generally a good level of group talk implementation (73% on the day of surveying) with lower incidence of 1:1 engagement during vaccination (56% on the day of surveying, with significant concern it is not happening consistently on other days).

We found moderate increases in client knowledge in two of the four key areas tested (risk of pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding). Intention to use a method of contraception increased by 7-12%, but this did not translate into contraceptive uptake which showed a 0 to -2% change. Higher abstinence rates in the endline samples may have reduced the likelihood of significant contraceptive uptake change.

Conclusions

Overall, the projects had a fairly mixed level of success, both in implementation and impact. Between the two, the postnatal care (PNC) intervention shows more promise given the higher reported rates of contraceptive uptake.

In particular, the 2-week follow-up results suggest a large shift in contraceptive behaviour (22% increase). How to treat these results is very unclear, given inconsistencies in the reported outcomes and possible surveying biases. As one example, this reported uptake greatly exceeds the reported intention to use – a trend that goes against established literature on the relationship between these two outcomes.

Additionally, we have significant concerns about the value of contraceptive uptake based on research conducted through the data analysis process. Very high rates of both breastfeeding and abstinence were reported across our surveying samples, with 75% of clients at CWC reporting prolonged abstinence. The combination of these two behaviours is likely to provide only a small reduction in protection from pregnancy compared to using a modern method of contraception. As such, it seems likely that contraceptive uptake at or shortly after a PNC session is providing little benefit to clients, greatly undermining the value of this project.

Concerns around high breastfeeding and abstinence rates would suggest that the CWC intervention arm is likely to be of greater value given it is reaching women who are further along in the postpartum period. However, this program performed poorly with no clear evidence of its value in driving knowledge change or shifts in contraceptive behaviour.

Overall, we believe these results do not suggest that the project should be scaled up given there is insufficient evidence of a strong positive benefit from the work and significant data quality issues. We are mindful of the time pressures on the Ghana Health Service and its staff. Given this, we do not feel that further implementation of changes to care that may increase the workload of frontline staff is justified without clear evidence of their value.

We will continue to investigate why this project did not work as well as anticipated, or as successfully as in randomised controlled trials from other places.

We welcome any further engagement with these results, this project, or the Maternal Health Initiative’s mission in general. Please do not hesitate to reach out through the contact details below.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many people who played a pivotal role in making this project possible. Thank you to Anthony Suguru Abako, Enoch Weikem Weyori, Abdul Rahman Issah and the rest of the Norsaac team for their resourcefulness and energy in delivering so much of the work on the ground.

Thank you to our skilful facilitator, Sulemana Hikimatu Tibangtaba, for delivering high-quality training sessions. Thank you to Sofía Martínez Gálvez and Catherine Fist for their insights and endeavour as MHI staff helping to design and implement this project. Thank you to MHI’s many volunteers and interns who gave up their time and energy for free, particularly Jemima Jones, Wan Yun Tan, Maxine Wu and Samuel Harvey.

Lastly, thank you to MHI’s donors and supporters, without whom this project would not have been possible.