The Importance of Birth Spacing

An introduction to the value of birth spacing, highlighting the important role promoting this plays in the impact of our work. Written by Samuel Harvey on behalf of MHI. Credit for photos to the Images of Empowerment project, unless otherwise stated.

Esther and her husband Francis squeeze into the back of a taxi at 3am – her pregnant belly only just fitting behind the front seat. “Kwahu Hospital please driver”, Francis says more calmly than he feels. Esther had known this moment was coming for eight months, but something was wrong this time. Her contractions were starting weeks earlier than she’d expected and they felt different from her previous labour.

The memory of her last birth flashed back to Esther. It was just over a year ago that they’d been blessed with a daughter. Things went well for her that time, but something told her things weren’t going to be as smooth today.

The realities of maternal mortality

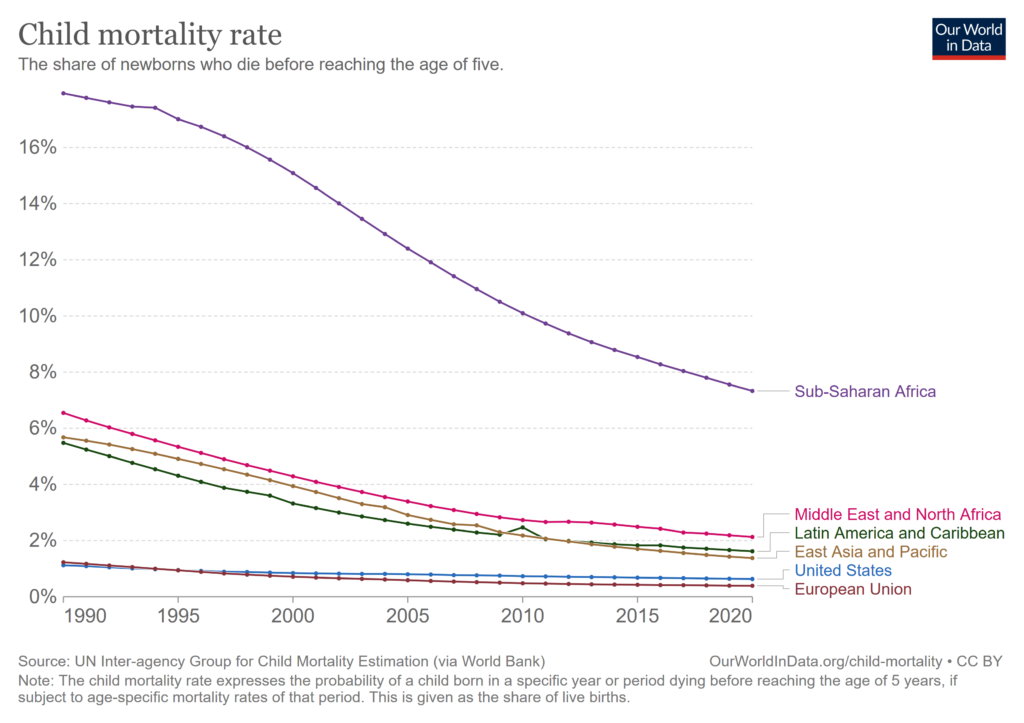

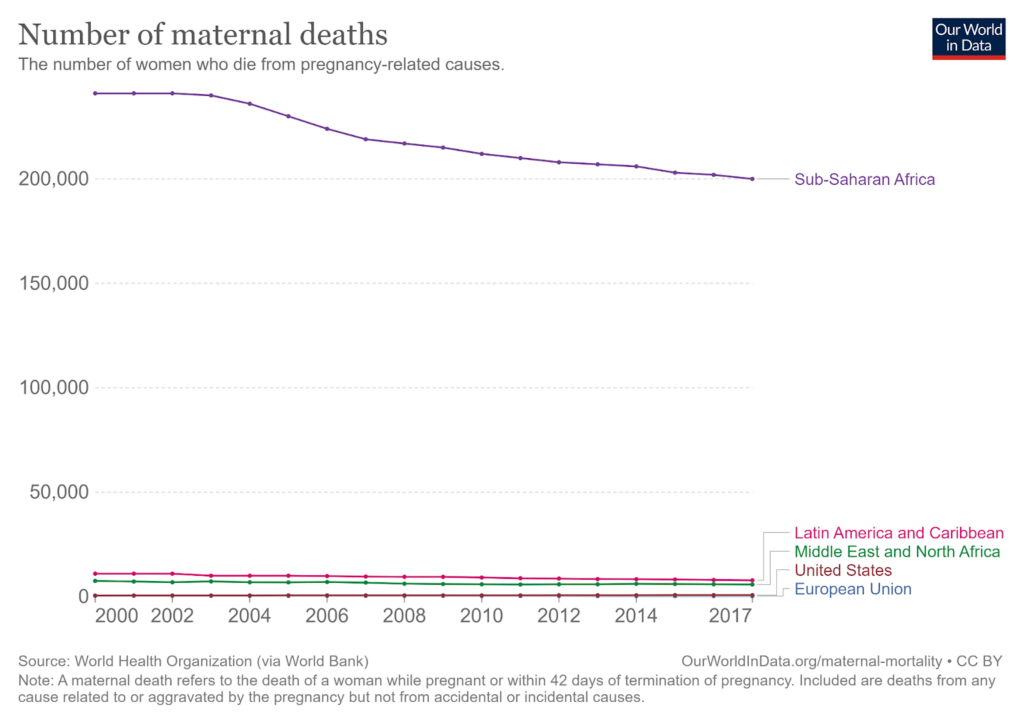

For many, it is easy to forget the tremendous risk that pregnancy and labour can pose to both mother and child. In the West – with our advanced sanitation and medical practices – each maternal and neonatal death is regarded as an unusual tragedy. But in some places, it is still a disturbing part of everyday life. Esther, our fictional woman from rural Ghana, has good reason to feel so frightened. In sub-Saharan Africa, one in fourteen children die before their fifth birthday [1] and one in 40 women will lose their life because of childbirth. [2]

Source: [3] Our World in Data. Child deaths by world region, 1950 to 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Feb 04]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality

There are many reasons why Esther and her child have the odds stacked against them. Key factors include higher rates of infectious disease, poor nutrition, and limited access to healthcare. One factor that may not immediately come to mind, however, is the short spacing between her previous pregnancy and this one.

‘Birth spacing’ is the amount of time between two consecutive pregnancies, with guidelines from the World Health Organisation recommending couples wait 24 months after a live birth before trying to become pregnant again [4]. However, a significant proportion of global births occur at much shorter intervals. A systematic review published in 2022 found that the frequency of short birth intervals in low and middle income countries (LMICs) could be as high as 66% [5].

Overall, our time in Sierra Leone was illuminating in understanding the specific successes and challenges of family provision in the country and the specific avenues along which MHI might best provide unique value. Our visit also proved fruitful in meeting with multiple potential partner organisations who can help MHI carry out preliminary research and testing work in the country, with whom we are currently finalising understandings of how we could proceed.

Why does birth spacing matter?

Lying on her hospital bed, Esther is drowsy and in a lot of pain but her thoughts are only with her newborn son. She cranes her neck to the left and sees a crowd surrounding the resuscitation trolley with her five-minute-old child in the centre.

The people surrounding her son go about their work with a calm sense of urgency. Someone is helping the tiny child breathe with a mask; another is wrapping monitor leads around his foot. Esther starts to feel light-headed. She tries to keep her eyes open but slips into a fitful sleep.

Stories like this play out in hospitals, birthing units, and homes throughout the world every day. Each terrible outcome is influenced by a combination of lifestyle factors, genetics, and bad luck. Compared with risks like smoking or malnutrition, something like birth spacing seems innocuous enough to hardly seem relevant. But the fact is this: short birth spacing kills mothers and children every day.

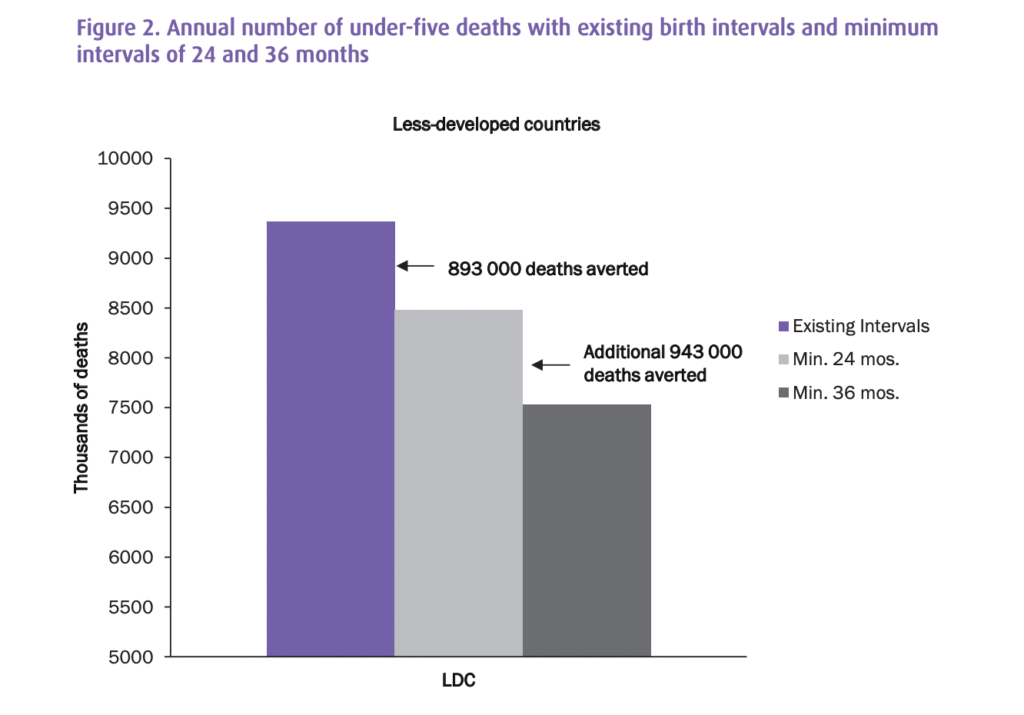

There is strong evidence that short birth spacing effectively doubles the risk of childhood mortality and stillbirths compared to adequately spaced births [5]. This contributes to a significant burden of preventable premature death in LMICs. In fact, a report from the World Health Organisation estimates that in less developed countries, almost 900,000 deaths of children under 5 years old could be prevented by spacing births at least 24 months apart, with a further 940,000 prevented with a spacing of 36 months. [6]

Source: [7] Rutstein SO. Further evidence of the effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal, infant and under-five-years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys. DHS Working Papers, Demographic and Health Research (41), 2008.

Short-spaced births also put an incredible amount of physiological stress on the mother. Without sufficient time to recover from a previous pregnancy, women are at increased risk of death and disease. This is mainly through increased rates of anaemia, postpartum haemorrhage, uterine rupture, and obstetric fistula. [8]

Adequate birth spacing can have a multitude of benefits beyond just preventing infant and maternal deaths. In the simplest terms, birth spacing can improve quality of life as a whole for both parents and children, while bringing significant benefit to women’s autonomy.

Parenting is challenging to begin with, and this challenge is compounded when juggling the needs of multiple children. People in developing countries likely face additional hurdles, such as financial insecurity, poorer health, and overstretched government support. Imagine you are Esther six months after the birth of her second child. Assuming a traditional family set up (as is common in Ghana), she is likely to be given the primary responsibility of looking after the children in these early years. Every day she will face many small decisions about where to put her time and money. 18 months is a very social age for a toddler, a time where they probably just want to play with mum, but Esther will also have a hungry infant who needs to be fed and therefore have less time to play. Maybe Esther would prefer to breastfeed the older child for longer but she doesn’t have the physical energy to feed both at the same time.

The financial decisions are also difficult. Perhaps they can only afford to send one child to school, afford fewer doctor visits between the two children, and have to ration food between the children at times to feed them both. Longer birth spacing gives breathing room to families, making these tough choices less common. Parents can allocate more time, energy, and attention to each child, resulting in improved wellbeing, health, education, and happiness.

Furthermore, adequate birth spacing can allow women additional time and energy to pursue activities outside of childrearing. Instead of being solely responsible for raising children, women have the choice to pursue other interests, such as furthering their education, starting a business, or advancing their careers. This can lead to increased economic independence and self-esteem, which benefits not only women but also their families and communities.

Why does short birth spacing negatively impact health?

After a while, Esther wakes up feeling groggy but relieved to see her son by her side. He is noticeably smaller than the other newborns in the room, but is breathing on his own and seems peaceful. She lets out a sigh of relief as she recalls the urgency in the room and the need for medical intervention. A nurse explains that Esther was anaemic and needed a blood transfusion, while her son required some help with breathing.

Happily, the nurse assures Esther that both she and her baby are stable now. Esther is grateful to have received the necessary care, but wonders how this could have happened, especially because her last pregnancy a year ago had gone so smoothly.

The health of a mother and her baby are intimately linked. In Esther’s case, research suggests that short birth spacing could have had a direct impact on her own health and the health of her new child. While the exact causes of these negative effects are not fully understood, observational studies have identified several possible mechanisms.

A potential cause of the negative effects associated with short birth spacing is maternal nutrition depletion. When a mother’s body is unable to fully recover from the demands of a previous pregnancy before starting a new one, there may not be enough nutrients for both the mother and the foetus. This creates a state of biological competition that puts both at risk [8]. This effect is even more significant in areas where nutrition is often inadequate. Interestingly, one study has found that the negative impacts of short birth spacing become less pronounced as the development level of the country increases [9]. This could provide further support for the hypothesis of nutritional depletion, as women in higher-income countries are less likely to experience malnourishment.

Another potential mechanism is sibling competition, where siblings that are close in age may compete for resources, parental care, and attention. This point about resource sharing is quite tangible in areas where access to food is legitimately limited and there may be significant rationing between children. The second point is less obvious but plausibly can increase stress levels for both the parents and the children, leading to adverse outcomes. In a similar vein, another suggested mechanism is that having more children around increases the chances of children spreading infectious disease between one another, therefore increasing childhood mortality.

Source: Hanna Morris on Unsplash

Birth spacing as a cultural norm

In our story, Esther had given birth within a year of having her last child. As we have seen, this is quite a common occurrence in some LMICs. This is not the story everywhere, however. The concept of birth spacing is certainly not new, and already a cultural norm in some parts of West Africa. One example is the concept of “Nef” in Senegal, which highlights a traditional emphasis on ensuring significant spacing between births.

A 2019 article explored the relationship between Nef, birth spacing and family planning by interviewing Senegalese men and women [10]. Nef was described most commonly as becoming pregnant while still breastfeeding, with the ideal length of breastfeeding being two years. Interestingly, this aligns with the WHO recommendation for birth spacing (24 months).

The overarching theme from the paper was that Nef is viewed quite negatively and carries a strong social stigma. One reason for this stigma is the poor health outcomes that Nef can inflict on a woman. Some of the beliefs discussed about birth spacing touch on the mechanisms discussed earlier in this post.

For example, interviewees often emphasised the importance of resting and regaining strength after childbirth:

“If a woman does not respect birth spacing it will cause health issues for her and she will have problems to take care of her children, she can develop anaemia because if we give birth each year we can develop blood problems.” [10]

In terms of why birth spacing is valued In the Senegalese context, it appears to be based on the way in which it strengthens her ability to adhere to the traditional role of mother by giving her more energy and time to better care for children and family. [10]

While this study focused on Senegal, it suggested positive attitudes towards longer birth spacing are widespread in West Africa, making it a natural fit for organisations to work with communities to promote positive change in this area. It is important to note that the local values and motivations behind birth spacing may differ from Western ones, and it is crucial to understand these differences when working in the region.

Barriers to birth spacing

There are a number of reasons why adequate birth spacing isn’t widely practised despite being beneficial and aligned with cultural values.

One factor is a lack of knowledge about its importance. In many places in Sub-Saharan Africa, good health information is hard to come by. Many women only interact with the health system very infrequently (often only when they give birth) and schools do not provide reproductive health information reliably. The health services that they can access may also be of poor quality and be inconsistent in providing family planning information.

There is also a general lack of understanding around modern contraceptives, leading to harmful misconceptions that drive hesitation in the use of family planning methods [11].

Finally, there is the problem of accessing contraceptives. Contraceptive availability varies based on the region and can be subject to supply issues. On top of this, while most contraceptives are relatively cheap, they are not entirely free. In a part of the world home to many of the poorest people on the planet, this barrier may be significant.

How MHI addresses this problem

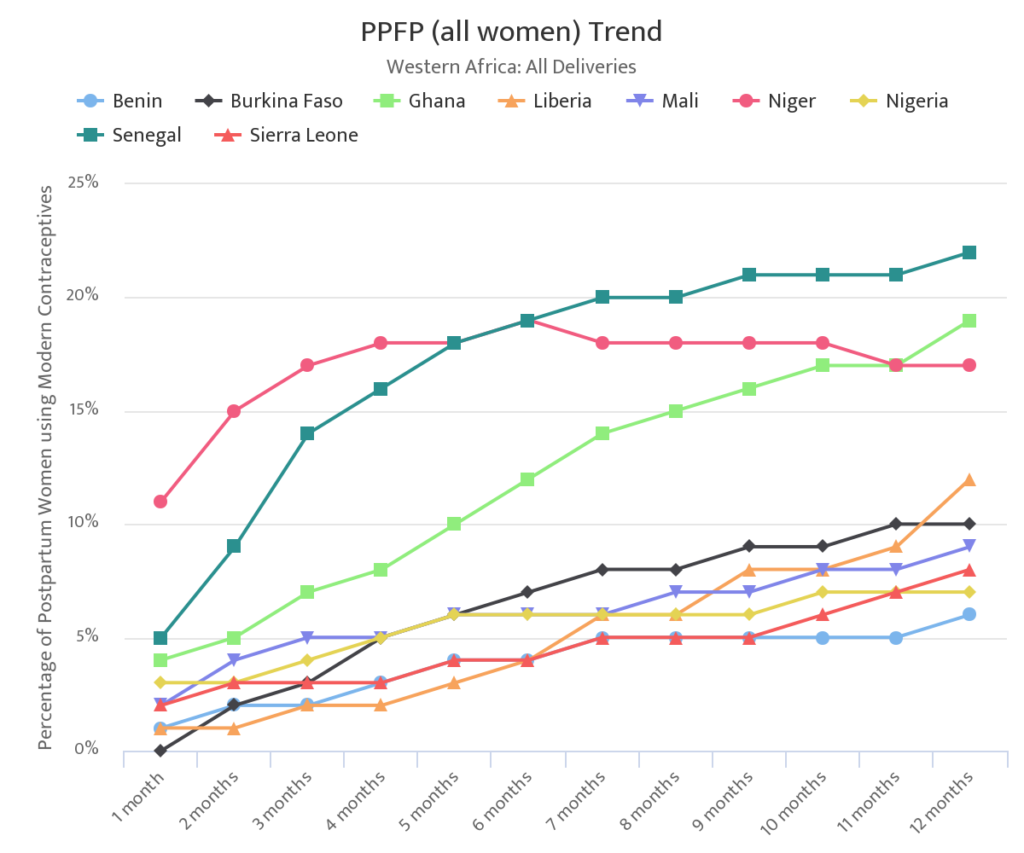

At the Maternal Health Initiative, we’re working to promote birth spacing by training health workers to provide family planning counselling in both the antenatal and postpartum period. The postpartum period is a particularly important touchpoint because contraceptive use is typically very low at this time.

One driver of this is an incorrect belief that it is impossible to become pregnant soon after childbirth when in fact fertility can return as early as four weeks after giving birth [12]. Beyond this, the only time many women interact with the healthcare system is when they give birth, which makes these sessions a unique opportunity to provide individuals with information and access to family planning solutions.

Source: Source: [13] Track 20. Trends in the Uptake of Postpartum Family Planning [Internet] [cited 2023 May 09] Available from: https://www.track20.org/pages/data_analysis/in_depth/PPFP/trends.php

MHI trains providers at health facilities to give up-to-date, evidence-based family planning advice so women like Esther can make informed decisions about the future of their families. By empowering healthcare providers with the knowledge and tools to provide effective counselling, we can support them in offering consistent information tailored to the needs and understandings of the women who they counsel.

Our current partnerships in the Northern Region of Ghana are helping us to test the best approaches to providing this training before we begin to scale this support across the country.

Inspired by MHI’s work? Please follow our work through our newsletter, reach out to us directly through our contact form, or consider donating to help us expand our work. Thank you for your support.

References

[1] Child mortality [Internet]. UNICEF DATA. 2023 . Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/under-five-mortality/

[2] Maternal mortality rates and statistics [Internet]. UNICEF DATA. 2023. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality/

[3] Our World in Data. Child deaths by world region, 1950 to 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Feb 04]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality

[4] World Health Organization. Reproductive Health and Research. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [cited 2023 Feb 04]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20170202023531/http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/69855/1/WHO_RHR_07.1_eng.pdf

[5] Islam MZ, Billah A, Islam MM, Rahman M, Khan N. Negative effects of short birth interval on child mortality in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2022 Sep 3;12:04070. doi: 10.7189/jogh.12.04070. PMID: 36057919; PMCID: PMC9441110. [cited 2023 Feb 04] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9441110/

[6] Bakamjian LCS, Cianci S, Malandrino C, et al. Programming strategies for postpartum family planning. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;13:23. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/93680/9789241506496_eng.pdf

[7] Rutstein SO. Further evidence of the effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal, infant and under-five-years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys. DHS Working Papers, Demographic and Health Research (41), 2008.

[8] Conde-Agudelo, A., Rosas-Bermudez, A., Castaño, F., & Norton, M. H. (2012). Effects of birth spacing on maternal, perinatal, infant, and child health: a systematic review of causal mechanisms. Studies in Family Planning, 43(2), 93-114. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00308.x. PMID:23175949.

[9] Joseph Molitoris, Kieron Barclay, Martin Kolk; When and Where Birth Spacing Matters for Child Survival: An International Comparison Using the DHS. Demography 1 August 2019; 56 (4): 1349–1370. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00798-y

[10] Duclos, D., Cavallaro, F. L., Ndoye, T., Faye, S. L., Diallo, I., Lynch, C. A., … Penn-Kekana, L. (2019). Critical insights on the demographic concept of “birth spacing”: locating Nef in family well-being, bodies, and relationships in Senegal. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 136-145. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1581533

[11] Hindin, D. J., McGough, L. J., & Adanu, R. M. (2012). Misperceptions, misinformation and myths about modern contraceptive use in Ghana. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 38(4), 251-255. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100464

[12] Jackson E, Glasier A. Return of ovulation and menses in postpartum nonlactating women: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:657–662. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820ce18c.

[13] Track 20. Trends in the Uptake of Postpartum Family Planning [Internet] [cited 2023 Feb 05] Available from: https://www.track20.org/pages/data_analysis/in_depth/PPFP/trends.php